We’ve all seen it. A line of athletes drags through a circuit of agility ladders, mat drills, and an endless succession of 20 yard shuttles as coaches scream about toughening up and being strong in the fourth quarter. Athletes stumble through drills looking at their feet, standing up straight, not using their arms. Put simply, they are in survival mode.

The goal here is to build speed, agility, strength, and the stamina to go all day long. While these goals all make sense and should be priorities, they cannot all be trained simultaneously.

Train for Sport Over Toughness

Mental and physical toughness is a valuable goal, but it can be developed without sacrificing development of speed and agility. Athletes who train in an aerobic fashion with infrequent to non-existent breaks are not getting faster or more agile. They’re not even being conditioned in a way that translates to football, basketball, baseball, or any primarily anaerobic (fast glycolysis) or phosphate system driven sport. Training in this way would only help them in a sport where they were expected to move at 60-70 percent effort for a long time with no breaks. This is not characteristic of most sports.

For example, the average football play is 4-7 seconds, with 35 seconds between plays. Baseball players are routinely asked to give a quick burst of energy, followed by a long complete recovery. This training approach completely misunderstands the way in which programs develop speed, agility, and sport-specific conditioning.

Form and Function Will Beat Fatigue

In order to improve speed and agility, athletes must perform drills with good form, and each action should be done at 100 percent effort. Therefore, each repetition should be done from a non-fatigued, fully recovered state. Sure, we demand that athletes give 110 percent in each drill, but as anyone who has ever worked out to exhaustion knows, you aren’t as fast or strong in a fatigued state. This is why coaches make the decision to give an athlete rest in a basketball game or why the star running-back usually does not play defense for the whole game.

For an athlete to be better conditioned to withstand fatigue, their conditioning must replicate the physiological demands of their sport. For most sports (cross-country being an obvious exception), running for miles will do little to nothing to improve an athlete’s ability to thrive or resist fatigue late in competition.

Many of you might be thinking, “In a game, the athlete will be tired and have to put together these movements at top speed.” This is true. However, the athlete will rely on improvements in speed or agility that were created in a non-fatigued state. Once these movement mechanics – increased neuro-muscular recruitment, rate of motor units firing, reduced stretch reflex time, and so on – have been programmed, then the improvements will be more available on the playing surface, even in a fatigued state.

The following factors will allow your athletes to use these improvements to greatest benefit:

- The amount of repetitions and practice they’ve put into the speed and agility drills while in a non-fatigued state

- How well conditioned they are to handle the physiological demands of their sport

Plan to Win by Planning Smart

So what about making your athletes tougher and better conditioned for the sport? This is an essential element of any off-season program, but it requires a little more creativity. The idea that, “If it is hard, then it is good for them” is the recipe for a tough team that is weak and slow. We are smarter than that.

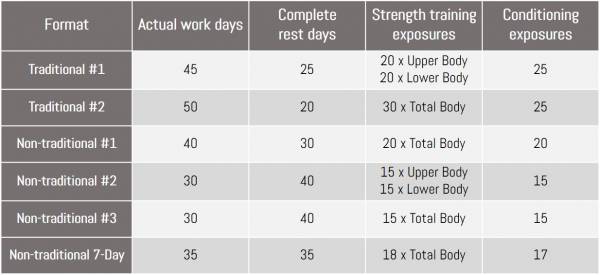

The first step to designing a conditioning plan is to plan. The plan should follow a periodization scheme, just like the resistance training plan. It should also match the physiological demands of the resistance plan.

Here are some pointers:

- Pair interval conditioning with high-rep hypertrophy phases and pair your low-rep max strength phases with short sprint, agility, and speed work.

- As you approach the season, make sure the conditioning builds on past phases while spending a bulk of the time replicating the metabolic demands of the competitive season.

Too many people just throw exercises and gadgets at their athletes. A good plan is organized and builds on itself while matching consistent training goals. It also builds to a comprehensive end point. Without these essential elements, the plan will underachieve, regardless of how good the exercise selection or equipment may be.

3 Must-Dos for Game-Ready Athletes

Here is a quick summary of the elements coaches must understand to get their athletes faster, more agile, and in playing shape:

1. Separate Out Training Variables

Speed, agility, and conditioning should not be trained simultaneously until close to competition. Agility work and speed work are not the same thing as conditioning. They require adequate recovery.

Use the principles of general adaptation syndrome (GAP) to guide your programming and recovery:

- Shock, Alarm, Resistance: This is how the body reacts to appropriate training. With proper recovery, the body enters the resistance phase and becomes stronger and better adapted.

- Shock, Alarm, Exhaustion: When not properly recovered, the body breaks down. Training has an effect like a sunburn. If the skin is burned and you don’t allow it to heal before subjecting it to another long bout in the sun, it will break down even more. Allow it to heal and it adapts with more melanin so that it is more resistant to future sunlight exposures. The body reacts similarly to resistance training and conditioning. 1

2. Use Progressive Overload

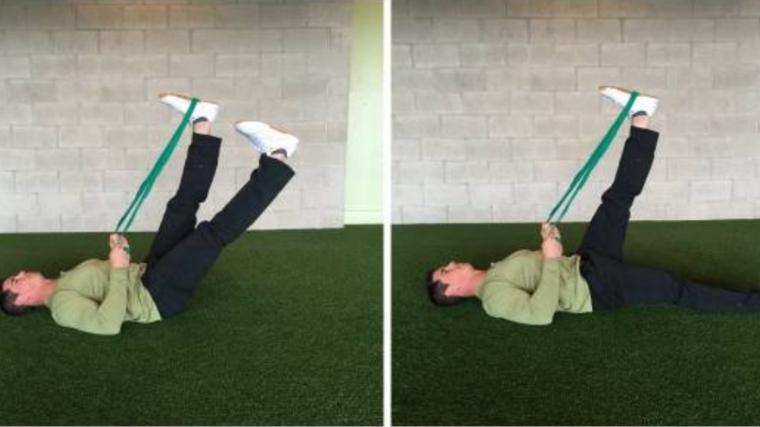

Start slowly and with perfect form. Hardwire this. Then increase volume or load. Do not attempt a program just because a successful athlete does it. High-level athletes can handle a lot more volume and technical skill-dependent exercises. The number one reason for not realizing big results in the weight room is poor form. Start with mastering the fundamental movements.

3. Remember: Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands

The body will only adapt to specific challenges that it faces repeatedly. In short, train for the specific improvement you want to see. Don’t make a shortstop run a few miles every week. This is also why ground-based training is far superior to a lot of the latest trends, such as stability balls and wobble boards.

World-renowned trainer Joe DeFranco elaborates on the training implications of this approach:

“In all of sports it is the athlete that moves while the playing surface remains still. Because of this, true ‘functional’ training should consist of applying resistance to an athlete while his/her feet are in contact with the ground. The athlete must then adapt to those forces.”2

So… stop running miles!

You’ll Also Enjoy:

References:

1. Brad Schoenfeld, The M.A.X. Muscle Plan. New York: Human Kinetics, 2013.

2. Joe DeFranco, Joe D. Talks Strength. Industrial Strength Podcast episode #15.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock

Photo 2 courtesy of Jorge Huerta Photogrpahy