Part dumbbell bench press and part isometric dumbbell flye, the hex press is a unique high-tension chest-builder. The hex press is performed on a flat bench with the dumbbells squeezed together throughout the pressing motion. This feature explains why one alternate name for this unique chest exercise is the “squeeze press.”

This exercise also goes by “Champagne press,” but the hex press isn’t just for special occasions. Like Champagne, the hex press compliments just about anything — it’s great for lifters training for a stronger press, a more muscular chest, or healthier shoulders.

Ready to pop the cork on new chest gains? Find everything you need to know below.

Hex Press

Hex Press Video Guide

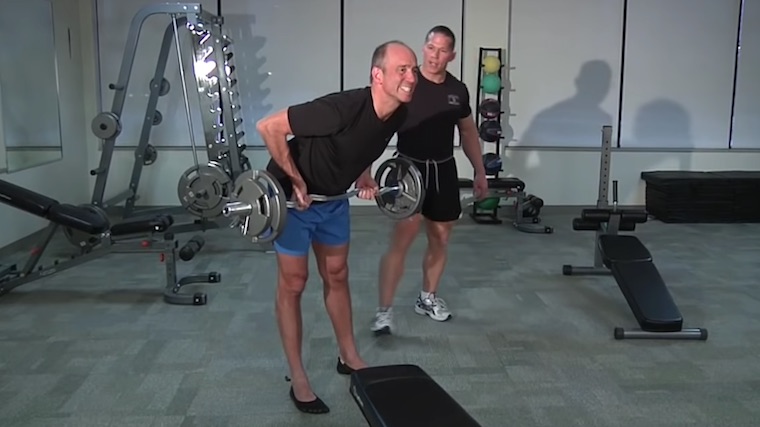

See the hex press in action, demonstrated by author Dr. Merrick Lincoln. Note the key techniques, then check out the Step-by-Step breakdown with additional form tips.

How to Do the Hex Press Step By Step

It may look like a close-grip dumbbell bench press but, while there are some similarities, there are crucial differences that make the hex press stand out. Follow these steps for proper, efficient, and effective technique.

Step 1 — Set Up Five Points of Contact

Like the bench press, the hex press is performed on a flat bench. Hold a dumbbell in each hand, set up with five points of contact for stability — the back of your head on the bench, your shoulder blades on the bench, your buttock on the bench, your right foot touching the floor, and your left foot touching the floor. (1)

Form Tip: Recruit a “spotter,” or individual who can assist you if you run into trouble during the exercise. Any exercise involving weights passing over the body requires a spotter. (1) A spotter is especially important when learning an unfamiliar exercise. The spotter stands behind the bench and, if assistance is necessary, they will assist by grasping your wrists to guide the dumbbells. (1)

Step 2 — Set Your Shoulders and Squeeze the Dumbbells Together

Lift your chest toward the ceiling by arching your back and pulling your shoulder blades together. Maintain this position throughout the exercise. With a neutral grip (palms facing each other), bring the dumbbells together just above your sternum and squeeze them together hard.

Form Tip: If you’re using hexagonal-shaped dumbbells — the namesake equipment for the hex press — ensure flat surfaces of the dumbbells are aligned and squeezed together.

Step 3 — Maintain Pressure, Press to Lockout

Initiate the press by flexing your shoulders and extending your elbows. Keep the dumbbells squeezed together and elbows tucked throughout the movement. Don’t decrease inward pressure as you reach the top, locked out, position.

Form Tip: Keep tension. In addition to the profound contraction you’ll feel in your chest, you should feel tension in your upper back and lats, which keep your shoulder blades pulled together (retracted) and keep your elbows tucked toward your sides.

Step 4 — Lower without Separating

Lower to the center of your chest using the same arm path as the upward movement phase. Focus on keeping the dumbbells firmly squeezed together throughout the lowering phase, which may feel slightly unnatural at first, since the lowering phase of most exercises emphasizes a muscle stretch.

Form Tip: Think about “rowing” or actively pulling the dumbbells back your chest. “Rowing” the weights back to the starting position reinforces tension in your upper back and eliminates the need to reset your arch before the next repletion.

Hex Press Mistakes to Avoid

Dodge these common errors for cleaner technique and more effective hex presses.

Losing The “Squeeze” Between Dumbbells

The pressure exerted between the dumbbells is part of the special sauce that makes the hex press effective — and extra spicy. It promotes muscular engagement in parts of the chest that might not otherwise be as active.

At the bottom position of the exercise, the lifter’s elbows are bent, and shoulder internal rotation force is required to keep the dumbbells together. Toward the top position, arms are straighter, and shoulder horizontal adduction force is required to keep the dumbbells together. Although it may get harder to keep the squeeze at the top and bottom of the movement, firm pressure between the dumbbells must be maintained throughout.

Dropping Your Chest, Freeing Your Shoulder Blades, or Flaring Your Elbows

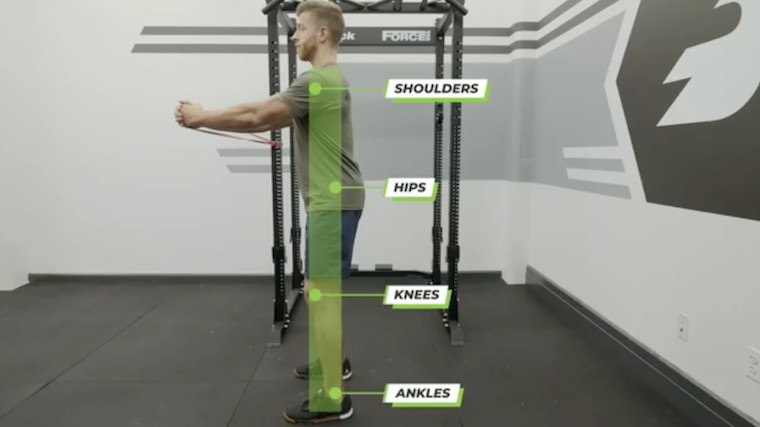

Loss of tension in the back allows the chest to drop, shoulder blades to spread, and upper arms to drift away from the lifter’s sides. These three errors tend to occur together, and they can make the hex press less effective.

If you feel any of these faults, reset by arching your spine, retracting your shoulder blades (and pinning them to the bench), and tucking your elbows toward your ribcage. Now, keep this tension and finish.

Non-Perpendicular Pressure Between Dumbbells

When squeezing the dumbbells together, it’s essential to maintain opposing forces from the left and right arm that are horizontally aligned and nearly equal in magnitude. Otherwise, dumbbells may slip or roll apart, leading to loss of tension, missed reps, or worse.

Get the feel of creating the squeeze using light dumbbells during your “work up” sets and focus on maintaining even, steady pressure throughout the workout.

How to Progress the Hex Press

When first performing the hex press, start with relatively light dumbbells to hone technique. Once you’re comfortable with the exercise, a “working weight” 20 to 30% lower than what you’d typically use for a traditional dumbbell bench press will likely be appropriate. From there, lifters have several great options for progressing the hex press.

Squeeze Harder

The simplest way to progress the hex press is to apply more inward pressure to the dumbbells. Increasing the “squeeze” makes the exercise more difficult and boosts the training stimulus experienced by the chest and shoulder muscles.

Increase Weight

Squeezing harder during the hex press can make virtually any weight more challenging, but this progression method isn’t likely to stimulate triceps growth or carry over to heavy pressing as efficiently as increasing the weight.

Once you’re able to hit or surpass your repetition target on the final working set, it may be time to use heavier dumbbells. Ideally, jumping up to the next pair of dumbbells on the rack will drop you back toward the bottom of your target repetition range.

Increase Repetition Volume

As you get stronger with the hex press, consider performing additional repetitions per set. For example, if you normally perform eight to 12 repetitions, and you’re consistently hitting 12 reps with more left in the tank, change your target to 12 to 16 repetition sets. Shifting the repetition range upward helps to ensure challenging sets and ongoing muscle gain.

Benefits of the Hex Press

The hex press biases your chest while requiring only light to moderate weights and minimal shoulder extension. Altogether, the hex press may provide new chest growth and a more shoulder-friendly pressing experience.

Robust Chest Training

Performed properly, the hex press enables maximal or near-maximal chest contraction throughout every repetition — a feat not possible during traditional presses. Here’s why:

Traditional exercises are limited by the amount of resistance our muscles can overcome during the sticking point, or the most challenging portion of the movement. For presses, the sticking point occurs toward the beginning of the upward movement phase. (2) During the remainder of the movement, your muscles are not maximally challenged. During the hex press, you can ensure your muscles are adequately stimulated by squeezing the weights together as hard as you desire.

Not feeling adequately challenged? Simply squeeze the dumbbells together harder to demand more force from the chest. Moreover, squeezing as you press virtually ensures thorough engagement of pectoralis major — Read more in the “Muscles Worked” section below.

Reinforces Mind-Muscle Connection and Pressing Technique

Horizontal pressing exercises, such as the bench press and dumbbell bench press, are a mainstay for strength training and physique development. Several technical elements are common across all bench-supported horizontal pressing exercises, including the need for shoulder blade retraction and co-contraction of muscles around the shoulder joints. Also desirable is the sensation of muscular effort from the chest. Lifters spend months, even years, honing their form to improve efficiency and effectiveness.

Fortunately, the hex press can help lifters to build strength, technique, and a mind-muscle connection that can reinforce proper performance of other horizontal presses. During the hex press, squeezing the dumbbells together creates the feeling of peak pectoralis major contraction throughout the pressing movement. This sensation of “flexing the pecs” can help to enhance the mind-muscle connection, which may be conducive to greater gains. (3)

Squeezing the dumbbells together also encourages greater involvement of your rhomboids and middle trapezius, as they must counteract forces from pectoralis major, subscapularis, serratus anterior, and other muscles on the front of the torso. Rhomboids and middle traps are the muscles primarily responsible for maintaining retraction of the shoulder blades. Increased demand during the hex press may encourage lifters to create a tighter setup for bench-supported horizontal pressing.

Shoulder-Friendly Pressing

Individuals with certain shoulder problems, such as shoulder instability, may not tolerate traditional pressing. (4)(5) Individuals who present with apprehension and pain in the front of the shoulder when the arm is brought out and extended behind the body may have a specific type of instability called anterior instability. (4)(6) This problem is common among lifters. One small study reported over two-thirds of recreational resistance trainees showed signs and symptoms of anterior instability. (6)

Unlike the basic dumbbell bench press or barbell bench press, the hex press limits shoulder extension at the bottom of the movement. Your arms cannot travel behind your body, because the dumbbells are not allowed to clear the chest. This feature may be better tolerated by lifters with functional anterior instability.

Because every brand of shoulder pain is different, those suffering with shoulder issues should seek a qualified sports medicine provider — and the hex press might be worth discussing, as it may present an opportunity to train around or train through certain shoulder issues with the appropriate guidance.

Muscles Worked by the Hex Press

As a neutral-grip pressing movement, the hex press trains the muscles that flex your shoulders and extend your elbows. Squeezing the dumbbells together also trains the muscles of shoulder horizontal adduction (i.e. those trained during a chest flye) and the muscles of shoulder internal rotation. Here are the major players.

Pectoralis Major

You’ll feel the hex press most profoundly in pectoralis major, the biggest, most superficial muscles of your chest. The pectoralis major has two major parts — the clavicular head, or upper chest, and the sternocostal head, which composes the middle to lower part of the chest. Each part contributes to various shoulder actions and the hex press covers virtually all bases for training your pectoralis major.

Shoulder flexion is resisted during the pressing movement of the hex press. The clavicular head of pectoralis major is trained during resisted shoulder flexion. (7) Shoulder horizontal adduction is trained by squeezing the dumbbells together toward the top of the hex press.

Both heads of the pectoralis major are trained during shoulder horizontal adduction, along with a handful of different muscles. (7)(8) Shoulder internal rotation is trained when the dumbbells are squeezed together toward the bottom of the hex press. Again, both heads are trained during internal rotation exercise, albeit the sternocostal head is likely biased. (9)

Anterior Deltoid

The deltoid is the “cap” of muscle surrounding the front, back, and side of your shoulder. It is divided into three functional parts, each with different actions — anterior, middle, and posterior. The anterior deltoid, or front delts, flex the shoulder and assist with squeezing the dumbbells together during the hex press. (7) While typical pressing exercises hit this part of the delt, the extra squeeze of the hex press makes this exercise more effective for anterior deltoid development.

Triceps Brachii

The hex press trains your triceps brachii, the three-headed muscle on the backside of your arms. In addition to filling your sleeves, the triceps brachii helps improve your bench press numbers by enhancing lockout strength. For a great triceps pump, try three or four sets of hex press with light-to-moderate weight dumbbells for high-repetition sets with 60 seconds rest between each set.

Rotator Cuff

Although traditional pressing largely trains muscles on the front of your chest and shoulders, the movement also activates important muscles located deep behind the shoulders— the posterior rotator cuff. (10) The posterior rotator cuff serves a stabilizing function during the press.

By actively squeezing the dumbbells together, particularly during the bottom half of the hex press, the deep muscle on the front of the shoulder, or anterior rotator cuff, is engaged. Hence, the hex press appears to be uniquely suited to train both the posterior and anterior rotator cuff muscles.

How to Program the Hex Press

The hex press can be programmed in a variety of ways on push day, during a specific chest workout, or during a full body workout. Hex presses can build muscle and strength. In addition, they prime your chest and shoulders for heavy work and work nicely for intensification techniques.

As a Low-to-Moderate Weight, High-Repetition Chest Builder

Whether training for building muscle (i.e. “hypertrophy”) or strength, high effort sets — those carried up to or near muscular failure — are effective even relatively with light weight. (11)(12)(13)

Select light-to-moderate weight dumbbells (e.g. 40 to 70% of what you’d use for a standard dumbbell bench press). Then, take each working set to within two or three repetitions of failure. Two to four sets of eight or more repetitions will promote strength and size, provided sets are performed with high levels of effort.

As a Lightweight Activation Exercise

Do you or someone you know suffer from the inability to feel the chest working during presses? Don’t despair. The hex press might be the fix.

Simply perform one to three light sets of hex presses before your primary press of the day (i.e. before the bench press, incline press, etc.). Focus on the “squeeze” during the hex press. Then, like an overfilled shaker bottle, the mind-muscle connection to your pecs will spill over to your primary pressing movement.

Maximally squeezing the dumbbells together during a set of hex pressing may increase power output during a subsequent set of presses via a phenomenon called post-activation potentiation. (14) This effect may be especially appealing for athletes and lifters training to be more athletic.

As Part of a Giant Set

A giant set is an intensification technique consisting of four or more exercises in series without rest between. Like supersets, the exercises used giant sets can target non-competing muscle groups or identical muscles.

When all four exercises in the giant set target the same muscles, they’ve been shown to produce similar hypertrophy to supersets and traditional sets that used 90 second rest intervals. (15) But here’s the kicker — giant sets take less time than supersets and traditional sets.

The hex press requires simple equipment, minimal setup, and compliments many different giant set configurations. Here’s a sample giant set:

- Dumbbell Bench Press — 3-4 x 12

- Dumbbell Pullover — 3-4 x 12

- Dumbbell Flye — 3-4 x 12

- Hex Press — 3-4 x 12

Take no rest between individual exercises. Switch dumbbells if necessary and immediately begin the next lift. Rest 60-90 seconds between giant sets.

Hex Press Variations

Looking for other effective and shoulder-friendly ways to train the chest? Depending on your preferences and available equipment, you might choose one of the following variations:

Single-Arm Dumbbell Floor Press

The dumbbell floor press can be a great exercise for learning and training horizontal pressing movements. Compared to the basic dumbbell bench press, the floor press limits shoulder extension, as the upper arms will be stopped by the ground. The shoulder extension range of motion of the floor press is similar to the hex press, meaning it is likely to minimize stress on the front of the shoulder, as discussed in the Benefits section, above.

One major drawback of the dumbbell floor press, however, is that it is usually limited to light dumbbells due to difficult setup. Performing the floor press one arm at a time (“unilaterally”) helps to minimize this problem.

Perform the single-arm dumbbell floor press lying on your back, either with your feet flat on the floor or your legs extended out in front of you. Begin the press with a single dumbbell held at the side of your chest and your upper arm resting on the floor. Keep your shoulder blades pinned to the floor as you drive the dumbbell toward the ceiling and lower with control.

Incline Hex Press

Limited research suggests the incline bench press may provide greater gains in upper chest, or clavicular head pectoralis major, muscle thickness compared to the flat bench press. (8)(16)

Although we must be cautious extrapolating these findings to the hex press, lifters wishing to build their upper chest might consider the incline version of the exercise. The incline hex press is performed just like the hex press, except an incline bench or adjustable bench set to approximately 45-degrees is used.

Hex Press to Flye Press Combo

A potential shortcoming of the hex press is the inability to expose the chest to training at long muscle lengths (e.g. “under stretch”). Enter the flye press. The traditional flye press involves pressing to lockout and then allowing the dumbbells to spread apart in a “flye-like” motion during the downward movement phase, thereby training pectoralis major at long muscle lengths during the eccentric (lowering phase).

For the hex press to flye press combo, get the benefits of the “squeeze” by performing the upward movement phase like a hex press and lowering the weights like a flye. Be sure to use lighter dumbbells than usual for this movement, as the eccentric flye is extremely challenging.

Medicine Ball Push-up

While this final variation isn’t a dumbbell press at all, push-up variations are criminally underrated. They can be done nearly anywhere. Better yet, push-ups increase strength and muscle mass similarly to the bench press. (17)

Performing push-ups with your hands on either side of a medicine ball requires isometric horizontal adduction of the shoulders similar to the hex press, while training through a similar pressing range of motion. Try the medicine ball squeeze push-up as a hex press alternative when dumbbells are scarce, when you want to change-up in the feel of your chest training, or when traditional push-ups become too easy.

FAQs

In bodybuilding speak, the “inner chest” refers to the fibers of pectoralis major that attach to the sternum. Specifically, those interested in building their inner chest are likely most concerned with the proximal or most central portions of those fibers.

Anyone who performs the hex press properly will tell you they feel a strong contraction of this portion of the pectoralis major. Although no studies have directly tested the hex press, let alone measured its long-term effects on chest muscle thickness, there is a case to be made for its use as an inner-chest builder.

Narrow-grip pressing tends to show lower muscular activity of the sternal part of pectoralis major compared to traditional or wide-grip pressing. (18) Although the arm path of the hex press resembles a narrow-grip or close-grip press, hex pressing involves the additional task of keeping the dumbbells squeezed together.

Therefore, it’s safe to assume the “squeeze” enhances sternal pectoralis major contraction, a feat lifters may be unable to accomplish during the traditional bench press. (19)

Although metal or rubber hexagonal-shaped dumbbells are common, many gyms have round or “pro style” dumbbells. The hex press can be performed with round dumbbells, as demonstrated in the video at the beginning of the article.

However, it is more challenging. Round dumbbells demand more precise application of inward pressure to avoid movement between the dumbbells.

That’s an option. Both exercises train pectoralis major, anterior deltoid, and company. But pec flyes are a single-joint exercise and fail to hit the triceps brachii, which does receive a training stimulus during the hex press.

Machine pec flyes and cable crossovers can also be more taxing on the shoulders, especially among lifters with functional anterior instability from a previous injury or cumulative trauma. This pathology is discussed in detail in the Benefits section.

The radius of the dumbbells gives the effect of a board press, which limits pressing range of motion. Specifically, shoulder extension is limited. Individuals with certain shoulder injuries, such as functional anterior instability, may not tolerate loaded shoulder extension. Hence, the hex press may be a suitable option.

Diving deeper, functional anterior instability is thought to be related to decreased activity of subscapularis — a muscle of the rotator cuff. (4) Squeezing the dumbbells together at the bottom of the hex press elicits strong contraction of the subscapularis. This feature might improve tolerance to exercise or help address subscapularis insufficiency.

Generally, hex pressing tends to be better tolerated than pec flyes and traditional bench press variations by those with banged up shoulders. Again, go see a qualified sports medicine practitioner if you’re dealing with a shoulder injury.

Build a Magnum Chest with the Champagne Press

The hex press is performed by aggressively squeezing dumbbells together throughout a neutral-grip dumbbell bench press. The squeeze engages greater portions of your pecs, which may lead to accelerated chest gains. The hex press also reinforces important elements of pressing technique, spares sore shoulders from loaded hyperextension, and creates co-contraction conducive to joint stability. Savor the squeeze and celebrate the hex press.

References

- Haff, G. G., & Triplett, N. T. (Eds.). (2015). Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning 4th ed. Human Kinetics. Champagne, IL, USA. 351-408.

- Kompf, J., & Arandjelović, O. (2017). The sticking point in the bench press, the squat, and the deadlift: Similarities and differences, and their significance for research and practice. Sports Medicine, 47, 631-640.

- Schoenfeld, B. J., et al. (2018). Differential effects of attentional focus strategies during long-term resistance training. European Journal of Sport Science, 18(5), 705-712.

- Moroder, P., et al. (2020). Characteristics of functional shoulder instability. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 29(1), 68-78.

- Kolber, M. J., et al. (2010). Shoulder injuries attributed to resistance training: a brief review. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(6), 1696-1704.

- Kolber, M. J., Corrao, M., & Hanney, W. J. (2013). Characteristics of anterior shoulder instability and hyperlaxity in the weight-training population. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 27(5), 1333-1339.

- Ackland, D. C., et al. (2008). Moment arms of the muscles crossing the anatomical shoulder. Journal of Anatomy, 213(4), 383-390.

- dos Santos Albarello, et al. (2022). Non-uniform excitation of pectoralis major induced by changes in bench press inclination leads to uneven variations in the cross-sectional area measured by panoramic ultrasonography. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 67, 102722

- Ackland, D. C., & Pandy, M. G. (2011). Moment arms of the shoulder muscles during axial rotation. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 29(5), 658-667.

- Wattanaprakornkul, D., et al. (2011). Direction-specific recruitment of rotator cuff muscles during bench press and row. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 21(6), 1041-1049.

- Schoenfeld, B., et al. (2021). Resistance training recommendations to maximize muscle hypertrophy in an athletic population: Position stand of the IUSCA. International Journal of Strength and Conditioning, 1(1), 1-30.

- Lasevicius, T., et al. (2018). Effects of different intensities of resistance training with equated volume load on muscle strength and hypertrophy. European Journal of Sport Science, 18(6), 772-780

- Weakley, J., et al. (2023). Physiological Responses and Adaptations to Lower Load Resistance Training: Implications for Health and Performance. Sports Medicine-Open, 9(1), 1-10.

- Esformes, J. I., et al. (2011). Effect of different types of conditioning contraction on upper body postactivation potentiation. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 25(1), 143-148.

- Demirtaş, B., et al. (2022). The effect of three different sets method used in resistance training on hypertrophy and maximal strength changes. Physical Education of Students, 26(6), 270-279.

- Chaves, S. F., et al. (2020). Effects of horizontal and incline bench press on neuromuscular adaptations in untrained young men. International Journal of Exercise Science, 13(6), 859.

- Kikuchi, N., & Nakazato, K. (2017). Low-load bench press and push-up induce similar muscle hypertrophy and strength gain. Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness, 15(1), 37-42.

- López-Vivancos, A., et al. (2023). Electromyographic Activity of the Pectoralis Major Muscle during Traditional Bench Press and Other Variants of Pectoral Exercises: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Applied Sciences, 13(8), 5203.

- Paoli, A., et al. (2019). Mind-muscle connection: effects of verbal instructions on muscle activity during bench press exercise. European Journal of Translational Myology, 29(2).

Featured Image: MDV Edwards / Shutterstock